We’ve Been Expecting You

We’ve Been Expecting You

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the whole world has been waiting for Vanuatu to take steps towards a unification of the various programs and pricing structures available for citizenship by investment in the Pacific island state. It’s a topic that, for too long, has been the subject of speculation, confusion, and doubt in the global investment migration industry – not to mention amongst the clients that have an interest in Vanuatu’s CIP.

In the past few days the simmering pan of discord and malcontent has looked as if it might finally boil over as an increasingly frustrated community of investment migration practitioners challenges the government in Vanuatu to come forward, to seize the narrative, and to demonstrate that local and global rumblings of discontent over the programs’ management and distribution have been heeded to, and acted upon.

It is, therefore, a much-welcomed development that – after some nine months of deliberations and drafting – the government gazetted a new pair of Regulation Orders on the 24th of April this year, both under the existing Citizenship Act (CAP112).

The Two Regulation Orders are as designated as follows:

- Citizenship (Development Support Program) Regulations Order No 33 of 2019

- Citizenship (Contribution Program) (Amendment) Order No 34 of 2019

These appear to be an earnest attempt to bring parity and clarity to Vanuatu citizenship by investment and, although doubtless there are still gaps to be filled, unresolved ambiguities and competing nomenclature, we are at last seeing a degree of convergence. The new Regulation Orders will dispel some of the fog surrounding the program, which has rendered it so difficult for the CIP-world to market it in a coherent, reliable fashion (except, it would seem, in Mainland China).

Why All The Fuss?

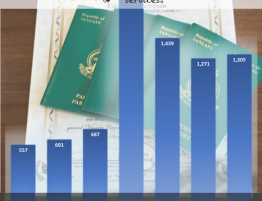

The Government in Vanuatu has – quite rightly – repeatedly referred to the fact that the Program is doing very nicely – pointing to the exponential growth of the Program in China – the impressive figures for which were recently revealed here by IMI Daily

But the citizenship by investment industry is at a critical juncture where so many components of the business are interdependent that it is imperative there be a shift towards uniform global standards and a degree of commonality in how CIPs are structured, managed, and distributed. For this reason alone, the new Regulation Orders are welcome, although there will be those who remain dissatisfied with what they’ll inevitably see as a “sticking plaster” solution to a much deeper malaise.

The Small Print

Given the noticeable growth in interest in the Vanuatu CIP, the two new Regulation Orders will be the subject of wide and close study around the world.

Whilst the following is somewhat “dense” text to anyone not planning to involve themselves in promoting the Vanuatu DSP, for those who are seeking to participate in this undeniably attractive program, the commentary could be useful (if dry) reference material.

Here, therefore, delivered with an impartial eye, is an attempt to bring into focus the most significant changes contained in the Regulation Orders, assembled by agents who have accumulated multiple-case experience and are intimately familiar with the process.

DSP v VCP

- Perhaps the most important aspect of the pair of Orders is the apparent aim to “harmonize” the applicant qualifying criteria, processing and pricing. It would take a deeper analysis and comparison with previous Orders to assess whether that aim is now fully achieved, but the intent is clearly there.

- The geographic focus reserved for the VCP versus DSP is not clearly addressed but, as territorial policing is all but impossible, perhaps this is no longer a factor in a price- and process-harmonized program.

- Assuming, therefore, that parity has been achieved, as there remains only one exclusive distributor of the VCP, we can disregard this program for the purposes of analysis and focus entirely on the DSP, assessing the amendments only to this option.

DSP Key Regulatory Revisions – a User’s Guide

Designated Agents (Clause 3)

Clarity on who can become a “Designated Agent”.

Selling Prices (Clause 4)

Perhaps the most important aspect of the DSP v VCP “harmonization” relates to pricing. New Minimum Retail Prices for both the DSP and VCP worldwide are stipulated. Vanuatu has a uniquely “layered” system for the distribution of its program, which accounts for the difference between the so-called “Government Prescribed Fees” and the “Minimum Selling Price”.

Upholding of Minimum Retail Prices (Clause 5)

Any agent found to be discounting the retail price or attempting to offer the Program at less than the minimum retail price may be reported to the Citizenship Commission and will have their license (and therefore any agent co-agreement) revoked.

Procedures for Applications (Clause 6)

A new outline of the Application Procedure is provided. The process remains much the same, but the outline offers some more specific timing guidelines than previously available.

Fee Payment Schedule (Clause 6(2) – 6(7))

In a rather unexpected move, regulations now mandate that an applicant may pay their Government “Prescribed” Fee in one of two ways. The following is only the author’s interpretation of the related regulations and may require further clarification:

- 25% of the prescribed fee prior to submission of the full (FIU cleared) application to the Citizenship Commission – with 75% payable after Citizenship Confirmation and, before issuance of the Citizenship Certificate.

- 100% of the prescribed fee upon submission of documents (as is currently done) to the Citizenship Commission for consideration.

The “show-stopper” here is the assertion that should the Commission refuse the application upon consideration by the Citizenship Commission Committee, then the 25% “down payment” made is non-refundable. This will certainly require more clarification.

Further, an additional paragraph (Clause 6(5)) states that the Commission must not consider the application of a person who has not paid as per Clause 6(2). As this renders the alternative payment method (Clause 6(3)) “non-admissible”, it can only be a mistake and will hopefully be rectified shortly by stating both the subclause (2) and (3) apply.

Applicants from Restricted Countries (Clause 6(8))

In a welcome modification to the current blanket exclusion of applicants bearing certain Nationality, a new Regulation is created which specifies that the application is admissible if the applicant has resided outside the restricted country for five years and in addition can provide evidence of permanent residency in a non-restricted country.

Non-circumvention (Clause 6(10))

A small, but important clause has been inserted to ensure that “ownership” of an applicant remains with the same agent throughout the process – unless the application has not been progressed in a satisfactory time frame.

Approval In Principle (Clause 6(11))

“Approval in Principle” is mentioned here – without it being clear at what stage this is granted. Once the Citizenship Committee meets and considers an application, the general understanding is that and approval granted here is final. We must assume this means “Subject to the remaining 75% of the prescribed fee being paid” where this route is chosen. However, in the case where the applicant has paid 100%, surely the approval is final. This requires further clarification.

Prescribed Fees (Clause 7)

This Clause is notable for the fact that the prescribed fees remain the same. Some ambiguity exists as the family categories mention only dependent children under 18 years of age – when in fact experience shows that combinations of children and resident dependents are permissible.

When referenced with the definitions under Clause 1, a clarification has been made regarding ages of dependent applicants as follows:

- Resident Dependent – Natural or adopted son/daughter 18-25yrs fulfilling the other stipulated criteria.

- Resident Dependent – Mother or Father of applicant or spouse who is over 50yrs fulfilling the other stipulated criteria.

Addition of Family Members “post” the granting of Citizenship under VERP/DSP (Clause 8)

This clause attempts to address the previously unclear Government policy for the adding of family members after the Principal Applicant has received Citizenship. The clause covers both the Honorary Citizenship DSP and the now-defunct VERP.

It should have addressed the specific case of a Principal Applicant who subsequently marries. However, this is in fact not directly addressed. “Spouse” is mentioned – without specifying if it means “existing spouse” (prior to Citizenship), or “future spouse” – a subsequent marriage after Citizenship obtained.

This Clause could be problematic as a potential “back-door” entry route to the Program for additional family members and should be the subject of further consideration and, as a necessary modification. As it refers specifically to the Honorary Citizenship DSP and the VERP, it might be argued that it does not apply to the Program in its re-designed form as per the new Regulation Order.

Pleasingly, the Clause specifically mentions that children born to applicants “post” the granting of Citizenship can be added at a nominal cost.

Citizenship Certificate Delivery (Clause 9)

Delivery of the Citizenship Certificate is delegated to the Designated Agent or his nominated representative. However, this does not address the cumbersome and unworkable passport delivery system which, as the popularity of the Citizenship Program grows will become unsustainable and impossible to manage given the huge geographical spread of applicants.

It is simply unworkable to expect hundreds of applicants to “crisscross” the globe to collect passports – not least because of the massive carbon footprint this generates – a subject that is close to the core interests of Vanuatu.

Likely the passport distribution aspect of the Program will be addressed elsewhere as the oversight of this is the remit of a different stake-holder.

The Final Word

There remains scope for considerable expansion of the Regulations and, therefore any omissions or perceived short-comings therein will be the subject of much further discussion. Two clear-cut areas that should have been addressed are the lack of clear directive regarding the removal of the “Honorary” Citizenship category, and the lack of reference to the admissibility of so-called “PEPs”.

Overall, the Regulation Orders do assist in clarifying, rationalizing and standardizing the Vanuatu DSP/VCP and will assist in growing the confidence of practitioners to represent the Program globally.

This feels like the next step in the evolution of the Vanuatu CIP, but external observers will likely keep pushing for a far more comprehensive “world-class” set of standards to conform with the most rigorously administered CIP structures.